4/5. killer of sheep

christopher funderburg

In October 2006, Funderburg and Cribbs set out to watch at least 200 movies over the course of the next 200 days. They both watched a different slate of films and wrote about every single one; from epic high art masterpieces such as Jean-Pierre Melvile's Army of Shadows to half-forgotten oddities like I Bury the Living to quality-deficient garbage like Charles Band's Tourist Trap. The Pink Smoke is reprinting their writings about the grueling experiment in cinematic endurance - due to the length of the essays, some of the entries such as Berlin Alexanderplatz and Grindhouse will be broken out individually.

<<click here for 3/22 - 3/31>>

4.5. Killer of Sheep.

(35mm) JBFC.

It would be impossible to understate how great this film is the only reservation I have about it is that some of the performances could charitably be described as "iffy." And on the surface of things, this would seem to be exactly the kind of film that wouldn't interest me: prominent ethnographic value (a real slice of life in Watts in the late 70's), a cast of non-actors, plenty of long and loosely improvised sequences, a pop-music driven soundtrack, critical assessments that emphasize its sense of the poetry of the working class. There's a lot there that's just not my scene, copache. It's conceivable that I never would have even seen it, if I hadn't stopped to drop off a paper to Professor Greg Taylor at the end of my Sophomore year of college.

Greg had set up a vhs video camera in the SUNY Purchase film program's small projection studio and was about to start taping Killer of Sheep off of the screen. It would, of course, be the most dubious, muddy transfer of the film possible, but this was back in 1999 and the film had been all but impossible to see for decades music rights issues had prevented it from ever being released on vhs or dvd and archives were unwilling to book it for anything but educational screenings. Even then, it was an arduous, shaky process, so getting even a 16mm print was a huge victory. I asked Greg what he was going to be recording off the screen. He described it. Yeah, not interested. But it was such a rarity I decided to stay for a couple minutes. I'm glad I did because it would be nearly a decade before I had any chance to see it again.*

Greg had set up a vhs video camera in the SUNY Purchase film program's small projection studio and was about to start taping Killer of Sheep off of the screen. It would, of course, be the most dubious, muddy transfer of the film possible, but this was back in 1999 and the film had been all but impossible to see for decades music rights issues had prevented it from ever being released on vhs or dvd and archives were unwilling to book it for anything but educational screenings. Even then, it was an arduous, shaky process, so getting even a 16mm print was a huge victory. I asked Greg what he was going to be recording off the screen. He described it. Yeah, not interested. But it was such a rarity I decided to stay for a couple minutes. I'm glad I did because it would be nearly a decade before I had any chance to see it again.*

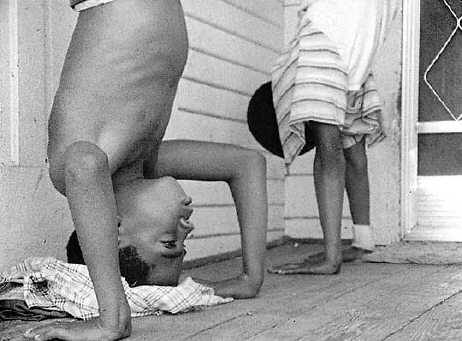

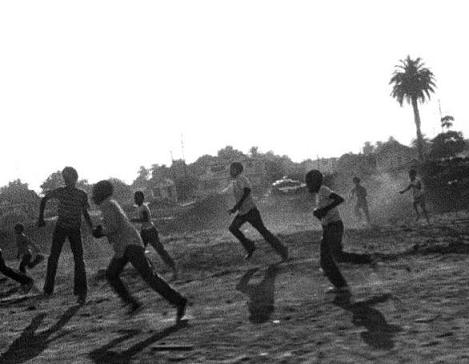

From the first scenes of kids having a dirt-clod fight in an abandoned lot, I was hooked. To this day, I've never seen a film so effortlessly capture what it's like to be a kid which makes sense because the filmmaker Charles Burnett simply turned his camera on kids as they played in the neighborhood. These totally unrehearsed, undirected scenes of kids playing are one of the many documentary touches that intrude on the narrative of the film, colliding with the scripted elements to create a poetry completely lacking in self-consciousness. And all of the stuff with kids is just incidental to the rest of the film, the gravy on the main plot's chicken-fried steak. That story mainly follows an insomniac slaughter-house worker played by a sleepy-eyed Henry Gale Sanders in his attempts to orchestrate a family day-trip out of the city. It would be tempting to make the plot of this film sound more substantial than it really is, but only because it feels so over-flowing with interesting incidents Sanders' attempts to get a new motor for his car are absolutely absorbing and fraught with peril, but never at the expense of intimacy or sincerity.

Contradictorily, the film feels so gigantic - epic even - because of its commitment to small details and truths. I mentioned poetry earlier and I think that's an important conceptual touchstone for Killer of Sheep. Most films function somewhat like prose: shots come together into larger scenes like words come together into sentences. Obviously, the metaphor isn't exact, but there's certain a standard way of constructing a narrative film, a bit of grammar** to framing compositions and editing them together you don't need me to tell you that a lot films start with Master Shot cut to an Over the Shoulder Shot cut to a matching Over the Shoulder cut to Close-up cut to matching Close-up. The meaning of a regular film is derived from its submission to this template of aesthetic construction the discovery of new phrasings is less important than using a standard grammar to convey a new idea or propel a narrative.

But with Sheep, the construction is purely poetic, in the sense that strange new phrasings and unexpectedly harmonious collisions are the aesthetic mode: the framing and editing of Sheep is wholly unique in the way that the language of e.e. cummings or T.S. Eliot is wholly unique. The emotional force as well as the meaning of Sheep is generated through poetic tactics its beauty is derived from a rhythmic, evocative, even mysterious manipulation of the form itself. It seems to be constantly searching for new ways of seeing, the way that a great poem seems to be searching for new ways of sounding.

But with Sheep, the construction is purely poetic, in the sense that strange new phrasings and unexpectedly harmonious collisions are the aesthetic mode: the framing and editing of Sheep is wholly unique in the way that the language of e.e. cummings or T.S. Eliot is wholly unique. The emotional force as well as the meaning of Sheep is generated through poetic tactics its beauty is derived from a rhythmic, evocative, even mysterious manipulation of the form itself. It seems to be constantly searching for new ways of seeing, the way that a great poem seems to be searching for new ways of sounding.

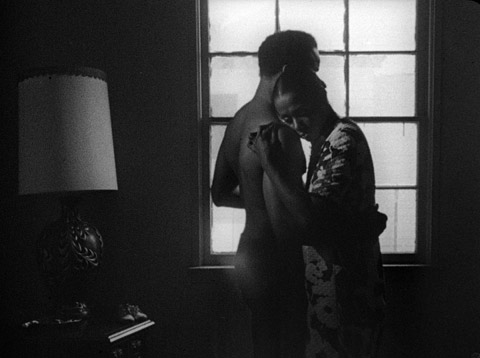

And then on top of that, the film has rigorous intelligence, an acute sense of the issues of class and race around which its characters contort and struggle. When Sanders tries to justify thinking of himself as middle-class by offering up that he gives clothes to the Salvation Army, it's a sad and funny bit that speaks volumes about the ways in which folks can overestimate their position in the pyramid of society. The tragic rub of his situation is that his fundamental decency does little to make his life an easier. However, the film is an ironic morality play that never implies that his decency is somehow making his life harder no good deed goes unpunished or punished in this film; life continues on, regardless of the sleepless nights. Sanders' performance in this context is truly remarkable. He lends an emotional accessibility to the proceedings that make this as intimately human a film as you will ever see. When he dances with his wife in their living room to "This Bitter Earth," it is heart-breaking and beautiful, tragic and hopeful I could easily spend the rest of my life watching movies and never again experience such a moment of connection with a film.

* I suppose I could've borrowed Greg's blurry vhs copy, but he was only making it so he could write about the film - that copy was a mess and barely even useful for such purely academic purposes, let alone trying to enjoy the film on an aesthetic level. Also, I should send a boatload of effusive praise to Dennis Doros and Amy Heller at Milestone Films for spear-heading the re-release. Also, Steven Soderbergh purportedly put up a bunch of money to clear up the music rights issues that plagued the film, which is awesome.

** I'm hesitant here because I think the idea of a semiotics of film is really over-played and images dont really function like words at all. I mean "grammar" almost entirely metaphorically - like there's a "grammar" to building a house or a "grammar" to composing a concerto.

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2010