Final Shots.

Part II by Ian Loffill

Casablanca. Dr. Strangelove. Planet of the Apes. Chinatown. Ask most folks what part of these milestone movies really stands out for them and they'll immediately mention the memorable last scene. And rightfully so - those endings aren't only satisfying, they punctuate and pretty much make you reconsider the entire film. In this series, The Pink Smoke examines some lesser-known finales we feel deserve a spot among the greatest final moments in cinema. Click here for Part I by Stu Steimer.

Pierrot Le Fou (Jean-Luc Godard, 1965)

It has always seemed like Jean-Luc Godard's cinema knew no conventional boundaries, barring the final credits of 1967's Week End which signify the end of cinema itself. Closing the adventures of Ferdinand and Marianne is a surprisingly lyrical final shot that is by turns shocking, absurd, comical, thoughtful and poetic. Moving from the explosion of Ferdinand's suicide on a clifftop, the camera pans to the right and a sight of the calm blue sea and sky. In one of Godard's most playful works, the film leaves us with a brief exchange between the two main characters on eternity and a moment of contemplation. It's a rare instance of imagery and dialogue being in perfect sync.

Damnation (Bela Tarr, 1988)

The central character of Damnation, whose motives and inaction are difficult to comprehend but all too believable, is given a stormy finale. From a fair distance we see Karrer, a withered soul alone and tormented by a selfish plan that backfired, walk aimlessly through a rainswept wasteland, briefly followed by a stray dog. The camera moves along slowly with Karrer exiting the frame (and the film itself) while the emphasis throughout remains on the loud rain, puddles and small hills of earth in the foreground. The stark and elemental imagery elevate the simple tale into something more timeless and troubling.

On Her Majesty's Secret Service (Peter Hunt, 1969)

Unique in the Bond series for many reasons, On Her Majesty's Secret Service ends with 007 as a broken man. Abandoning the pulpy tone and carnal humour that wrapped up earlier (and indeed later) offerings in the series, OHMSS closes on a shot of a bullet hole through Bond's car windscreen. Having cut away from the most tragic moment in any Bond film, it's an apt final image that reflects the hero's grieving and wounded psyche. So effective is this last shot (which has become such an iconic image of the Bond canon it was used for the teaser poster of the upcoming film, SPECTRE) that it also makes you realize what a horribly wasted opportunity the following Bond film, 1971's Diamonds Are Forever, ended up being.

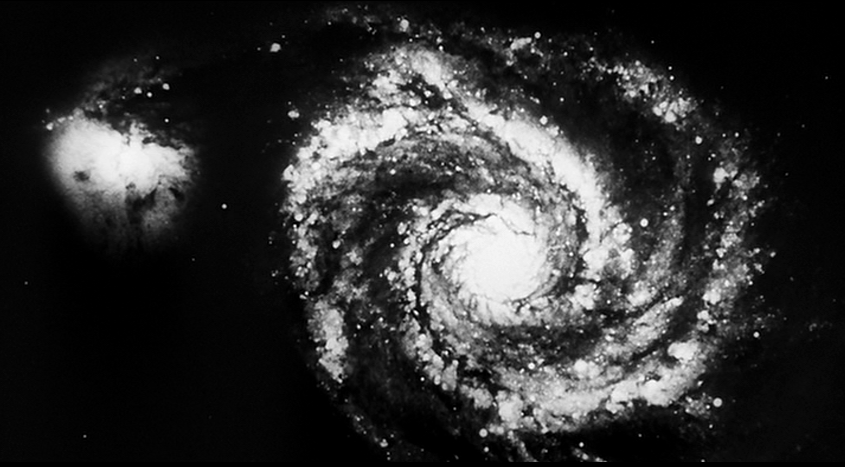

The Incredible Shrinking Man (Jack Arnold, 1957)

I looked up, as if somehow I would grasp the Heavens, the Universe, worlds beyond number....

Although not happy with the film at first, screenwriter Richard Matheson realized years later how unusual it was for its time, especially the ending. It's the one ending in film history that, more than any other, floors me every time I see it. In an extraordinary final monologue, allegedly written by director Jack Arnold and not Matheson, Scott Carey (played by Grant Williams) moves from fear to acceptance about his fate of going down into the microscopic world. A closing shot of infinite possibilities, the film takes us outside Carey's house and garden to a view of the stars, outer space and beyond, suggesting anything from total oblivion to an exciting new dawn. Over a decade before Kubrick's 2001: A Space Odyssey, here was a film unafraid to show us mankind's place in the Universe and view human concerns on a cosmic scale.

Escape from Alcatraz (Don Siegel, 1979)

In a sense this was always going to be a tough one to wrap up, but the final collaboration between Clint Eastwood and Don Siegel ended on an ambiguous note both on- and off-screen. According to Marc Eliot's biography of Eastwood, the ending was a late addition in the film's production and came from the star rather than the director. Eastwood once mentioned how Siegel had an ear infection problem, and had already started work on another film, so he entrusted the actor (by this stage an experienced director in his own right) to take over the post-production process as much of the work had been done already. Siegel and Eastwood were in agreement on the concept and screenplay, but the changes - including Siegel's cameo being cut out of the film - may have caused a rift between the two. For the final moments, Siegel's alleged idea was to stress the bleakness of Alcatraz itself and end it inside the prison; Eastwood wanted to bring it outdoors and focus on the uncertain fate of the prisoners, who may have gone to a watery grave off Alcatraz Island or spent the rest of their lives on the run.

In the finished film, the warden (played by Patrick McGoohan) discovers a yellow chrysanthemum on a rock on Angel Island during a search the day after the escape. In frustration he crushes the flower and throws it to the waves while a closing note informs the audience of the prison's eventual closure and how the fate of the three prisoners who escaped remains unknown. The flower has been a symbol throughout the film for all the prisoners who endure this harsh environment. It is used by Doc in his own painting, his one privilege and joy in prison life. For Eastwood's determined Frank Morris, it may be a sign of hope that he will eventually get off the godforsaken island. For the warden, it's a mark of defiance and a final mocking gesture from Frank Morris. For the audience, it poses many questions and gives Eastwood's trademark anti-authoritarian character the last laugh.

RELATED ARTICLES

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2015