MATHESON MONTH ~

ian loffill

In tribute to the recently departed Richard Matheson, The Pink Smoke has dubbed this October "Matheson Month."

We'll be taking a look at some of the films written by the esteemed novelist and short story scribe (I Am Legend, The Omegae Man, The Twilight Zone), whose work has influenced and continues to shape the horror movie genre.

THE LEGEND OF HELL HOUSE

john hough, 1973

The Legend of Hell House, adapted by Richard Matheson from his 1971 novel Hell House, had a very quick journey to the big screen. It began filming in October 1972 and was released in June 1973, several months after the death of producer James H. Nicholson.* Almost from the beginning, Matheson the author put his fate in his own hands where film adaptation was concerned

when he agreed to sell the rights to The Shrinking Man on the condition that he could write the screenplay himself. He maintained a prolific output as a screenwriter in film and television throughout the '60s, '70s and '80s, forming a sort of parallel career with his published works. So experienced was Matheson by this stage with the page to screen process it's quite possible that the author had a motion picture version of Hell House in mind when he wrote the book.

Matheson was on familiar ground with a novel and film like Hell House. He was well versed in Gothic and supernatural matters while working with Roger Corman, AIP and Hammer Studios and had adapted the works of authors like Poe, Fritz Leiber Jr. and Dennis Wheatley for the screen. Director John Hough was a decent enough choice given that he too was obviously drawn to material of this type. Having worked his way up from second unit jobs on British television to

directing for Hammer with the vampire film Twins of Evil, he would later go on to helm Escape to Witch Mountain and The Watcher in the Woods for Disney. His career took a trashier turn in the 1980's with demonic horror flick The Incubus and Howling IV: The Original Nightmare.

It's incredibly difficult to discuss The Legend of Hell House without at least mentioning both Shirley Jackson's 1959 novel The Haunting of Hill House and the brilliant 1963 film adaptation The Haunting. Much as Matheson's novel stands in the considerable shadow cast by Jackson's classic tale, John Hough’s film is frequently judged in relation to Robert Wise's. This is hardly a surprising fate given that both share an extremely similar storyline

of four people investigating a notorious haunted site as part of a study and in the process simultaneously question their own beliefs in science and superstition and confront their worst fears. Hell House has been described by Stephen King as "the scariest haunted house novel ever written." I feel it's far too indebted to Jackson's work to stand as a classic in its own right. Passages from the book like "Hell House should be burned to the ground" inevitably sound overly familiar.

It was the encapsulated review in Halliwell's Film Guide - "a less solemn but more frightening version of The Haunting" - that really grabbed my interest before I saw The Legend of Hell House for the first time years ago. A film that is more frightening than The Haunting? That's a pretty bold claim. On this basis, my first viewing was inevitably a crushing disappointment. Paradoxically, I don't usually watch horror films expecting

to be frightened. If that happens then great, but as dull as it sounds I'm more interested in horror films that examine the nature of fear than ones that make me jump out of my seat. Even though most horror films are sold on their promise to terrify and disturb the audience, I've always found that expectation to be the wrong way to approach films of the genre. It gives the viewer a more guarded approach, expecting something to jump out of the shadows and instead being made to study the build up of suspense and

unease rather than experiencing it.

As usual with these things there is much detail in the novel that gets barely hinted at in the film or in some cases is dropped completely. The action is moved from the United States to a U.K. setting, but this change is of little consequence. The investigation in the Belasco House is initiated and funded by aging millionaire Rolf Rudolph Deutsch - he offers a financial reward to find out the facts about survival after death in "the Everest of Haunted Houses"

over the course of a week in December. The four investigators are physicist Lionel Barrett, his wife and assistant Edith, physical medium Ben Fischer (the traumatised sole survivor of a previous investigation at Hell House in his childhood) and spiritualist medium Florence Tanner.

In the film Florence is much younger, giving her a more naïve quality, while Lionel's disability, a source of considerable pain and discomfort in the book, is dropped completely. The antagonism between the four characters is greater

in the novel, but Matheson seems eager to get down to business in the movie and cuts out much of the squabbling. Once we establish the tension between Lionel and the two mediums, the film pretty much moves on. The book seems to linger on it, turning the whole thing into a debate.

While the book feels overextended, the film is curiously underdeveloped. It occasionally hints at backstory and character information in subtle ways, but at times a real lack of detail and context is evident. In this respect, the book certainly compliments the film. So much detail is cut out we don't really get to know the characters as well as we should. Most notable for me is the short shrift given to Deutsch in the opening scenes. His ailing condition and the sense

of urgency for the dying man to acquire this knowledge are far clearer in the book.

One of my favourite parts of the novel is towards the end when the unexpected death of Deutsch is mentioned over the phone to a pained Lionel, who had initially called for an ambulance. It is one of those crushing, darkly humorous moments that illuminate the lunacy and futility of it all. The ostensible reason for the investigation has gone; Deutsch's assistant even makes it pretty clear that they are unlikely to see the money

reward that was offered as there was no contract to begin with. It makes the characters aware that they have deeper motives for this undertaking, and after all they've been through there can be no turning back. The film omits this brief episode which I feel is a mistake. Meanwhile it maintains the time/date check episodic structure of the book, an efficient but overused device, maybe intended to give us a sense of the scientific report that is in progress.

Perhaps following Robert Wise's example, Hough employs unusual camera angles, sound effects and lighting to suggest something amiss in Hell House, but it doesn't quite get under our skin the way it should. Despite some creepy low angle exterior shots, the details of the Belasco house aren't particularly interesting on the inside. It never really becomes a character in the story, like Hill House does in The Haunting (there I go again) or in the way

the Overlook Hotel casts its spell in The Shining. There is much here that is effective – the shadowy apparitions that disturb and arouse Edith is a good example of how the film approached the explicit sexuality and Sadian aspects at the heart of the novel in a more suggestive than graphic way.

The conflicting views of Lionel, who refuses to accept anything that contradicts his life's work, and Florence, whose openness to the influence of the house and her belief that the tormented spirit of Belasco's

dead son provides the key to Hell House's mystery brings terrible consequences. Fischer's reluctance to engage with the experiments until the later stages makes him more of a guarded spectator to events. However as soon as the occurrences at the mansion take a sinister turn there's little room for pause and it becomes a series of incidents and shock effects done with varying success. We're simply left wondering what ghastly events will take place in the house next rather than worrying about the fates of those

inside. The toll the house takes on the guests isn't particularly clear; from one scene to the next they go from calm to hysterical to bemused. Pamela Franklin, already a horror icon as a child actress for having appeared in The Innocents and Hammer production The Nanny, gives by far the best performance as Florence Tanner. Had there been more focus on Tanner, her determination and her transformation from a mental medium to a physical medium it would have been a much more effective film.

Writers are often an undervalued part of the filmmaking process, but Matheson's name always adds a layer of interest to a film for me, whether he provided the source material or the screenplay. The Legend of Hell House is less engrossing than other Matheson tales. The slow build up of tension, mounting dread and unfolding narrative of, say, Duel or the legendary Twilight Zone episode Nightmare at 20,000 Feet just isn’t there. Matheson,

to his credit, was pragmatic about its failings and admitted that something in his screenplay was wrong, although he wasn't sure what it was exactly.

For me, the problem is in the source material itself: its lack of mystery and reasoning approach becomes a hindrance towards the end. Matheson was one of the pioneering writers who helped bring horror into a truly modern setting, and that approach still resonates with audiences. Finding a rational basis for seemingly unexplainable phenomena and supernatural events

was one of Matheson's great gifts as a writer. Whether it was a plague that created a world swarming with vampires or a cloud of radioactive spray that causes an average man to shrink to microscopic proportions, Matheson liked to ground his stories in their own logic and reality. He seemed to be going against the belief exhorted by H.P. Lovecraft that in all matters mysterious "never explain anything." The trouble with Hell House (novel and film) is that Matheson explains far too much.

Here the conflict

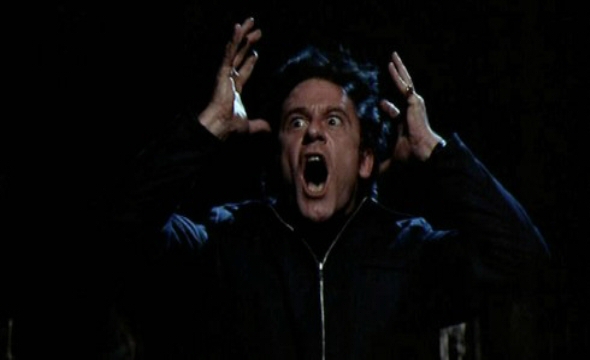

between scientific and spiritual views is neatly resolved but the payoff is unsatisfactory to say the least. It seems too keen to reveal its secrets in the final stages, and Roddy McDowall as Fischer is given free rein to overact at the film's rather limp conclusion. Fischer's final explanation for the cause of the evil that dwells inside Hell House is not far removed from something out of a Scooby-Doo episode.

In some ways Hell House was a vital turning point in Matheson's career, and it's easy to see why he decided on a change of direction. After Hell House, Matheson’s fantasy fiction went from speculating on scenarios in a world broadly recognizable as our own to a world beyond. Moving on from this life to the next and finding possible links between the two, he would go on to adopt a romantic approach to tales of time travel (Bid Time Return,

later filmed as Somewhere in Time) and the afterlife (What Dreams May Come). In subsequent novels such as Earthbound and Other Kingdoms, he returns to the themes of parapsychology and paranormal matters time and again.

Given Hell House's tendency towards theories and speculation, it could be that Matheson's interest in these matters (early signs of which appear in his 1958 novel A Stir of Echoes) got in the way of a more successful work. The scientific approach to

ghostly subjects has held an ongoing fascination for filmmakers and writers, notably in the 1972 TV film The Stone Tape and again in Poltergeist ten years later, amongst others. It would seem that Matheson had high hopes for his haunted house tale and its big screen version. Later on he said, "The first time I saw it, I was sick with disappointment and I just couldn’t get over it for weeks." Over time he came to see it in a more positive light.

At first I, too, was overly critical

of the film and, seeing it again years later, I can now appreciate its merits. If it sounds like I'm dwelling too much on the flaws, it's because it lacks much of the ingenuity one usually associates with its author. The film revels in showing us black cats, mist, cobwebs, creaking floorboards and blood dripping from the shower. I like such details in films, but it was a sign that the horror clichés that Matheson once transcended were now appearing in his work. A certain intellectual boredom with the genre may

have been creeping in by this stage and Matheson wisely looked elsewhere to fulfill his spiritual and otherworldly obsessions.

~ OCTOBER, 2013 ~

* Nicholson had just left AIP, home of Matheson's Poe-related pictures. He set up shop at 20th Century Fox with five movies he intended to produce, only two of which - Hell House and Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry - realized prior to his untimely death.