little-loved altman.

In this nine-part series, The Pink Smoke will be plumbing the murky depths of the filmography of legendary director Robert Altman, a master of le cinema who in his wildly inconsistent career created not only some legendarily awful movies, but at least a dozen films overlooked and half-remembered even by his admirers. We'll be skipping consensus "secret masterpieces" like California Split and Secret Honor in order to focus on his most polarizing, universally despised and simply forgotten films.

prêt-à-porter by christopher funderburg

Going into the production of Prêt-à-Porter, Robert Altman was on a bit of a roll. As it had been for many of the celebrated New Hollywood filmmakers who determined the cinematic zeitgeist in the 70's, the ensuing decade had been a bit of wasteland for the bearded, balding impresario of ensemble. But starting with his well-regarded (but little-seen) t.v. project Tanner '88, Altman had begun to regain a bit of his footing: he followed that series with the well-reviewed Vincent and Theo in 1990 then moved on to the two biggest hits of his post-70's career. The Player and Short Cuts re-established Altman as a titan of le cinema, his clever, self-referential thriller and the ambitious adaptation of an adored author's short story collection both the type of work that combined artistic risks with a strong commercial dimension – the kind of art cinema that could make real money, Hollywood's favorite kind of art cinema. While neither film quite attained the cultural touchstone status of M*A*S*H or Nashville, they certainly saved Altman's reputation and prevented him from becoming another Arthur Penn or William Friedkin, an irrelevant relic of a bold 70's Hollywood filmmaking culture that no longer even slightly existed. The run from Tanner to Short Cuts represented a striking rejuvenation, all the more surprising for not being a reinvention: after 15 years of sputtering, Altman had suddenly found a way to make "Altman movies" again, raucous ensemble satires graced equally with unforgettable performances and circuitous, unpredictable narratives. Prêt-à-Porter shot his resurgence directly in the skull, stopping it in its tracks dead as dead could be. Prêt-à-Porter presaged a futile 7 years of pseudo-Altman movies where the man who perfected the style couldn't seem to land on the same continent as "brilliant ensemble satire" and instead turned out junky, jokey, broad, bad misfires like Cookie's Fortune and Dr. T and the Women that could only helplessly gather together large casts and give them cacophonously unfunny things to do. The elevation of Gosford Park in 2001 to the level of "classic Altman" has always seemed to me more like charitable gesture towards a beloved filmmaker more than an actual assessment of the film itself: it's fine, nothing special, but I think folks were relieved that Altman could still even produce such a modest success. Prêt-à-Porter was a doubly unfortunate thing to inflict on audiences not only because it portended the coming return to the dark ages for Altman but because it arrived just at the moment audiences began to feel hopeful that Altman the Genius had decisively returned. If it had been a blip on the radar coming between The Player and Short Cuts, maybe it wouldn't have been such a crushing experience for critics and fans expecting it to be good.

I saw it as a teenager at the Christiana Mall in the absurdly-named area of Metroform, Delware. That it was playing at a mall means it received a pretty expansive release and the distribution company behind the film (Miramax) didn't expect or intend for it to be a niche product. Harvey Weinstein's Miramax would have their breakout hit the same year with Pulp Fiction and while that film would significantly change the landscape of film distribution, the shift was already underway in 1994: mini-major corporations like Miramax, New Line Cinema and October Films were trying and frequently succeeding in making big money off of little films, $10 million grosses and higher off of films it cost them pencil shavings to pick up and distribute. In some ways, Prêt-à-Porter fell victim to the new "hey, we can make money off of this stuff!" mindset that led to gigantic corporations opening boutique divisions or buying up smaller distributors, going bananas in bidding wars at film festivals and then pouring money into the marketing and distribution of formerly arthouse-bound fare. Altman had been one of the initial "artistic" filmmakers to find massive commercial success in the 70's making uncompromising films, so pimping his latest made business sense for Weinstein, who excels to this day at carving out (lucrative) space between the world of blockbuster product and art. With Prêt-à-Porter, Weinstein's promotion screamed "here it is, the next huge Altman hit!" The poster even had a naked supermodel on it.* But pushing Altman's fashion-world satire for mainstream success (and putting it in fucking malls in Delaware) was based on a fallacy: three or four films aside, Altman's movies had never made any money. M*A*S*H, of course, made bank and spawned a massively popular television show (and I wouldn't put it past Weinstein to have imagined a sitcom spin-off of Prêt-à-Porter), but Altman’s other hits like Nashville and McCabe & Mrs. Miller were modest hits in comparison to the blockbuster successes of the era like Easy Rider, Bonnie and Clyde, The Exorcist, The French Connection and Jaws. In fact, the entire idea for this series is that if you look at Altman's filmography, it's fascinatingly littered with films despised by critics and audiences alike. Many of his best films, California Split or Thieves Like Us, failed to make an impact at the box office and many of his more ambitious experiments like 3 Women and Brewster McCloud divide audiences into camps of shouting at each other "I love this movie!" and "If this movie were Vincent Gallo, I would puke on its cock!" Despite The Player and Short Cuts, expecting Altman to deliver a hit constituted a very bad bet. If anything, two financial successes in row almost guaranteed he would deliver anything but a crowd-pleaser, fan-favorite or critically-lauded masterpiece. My mom made me apologize for having her drive me to Delaware to see it.

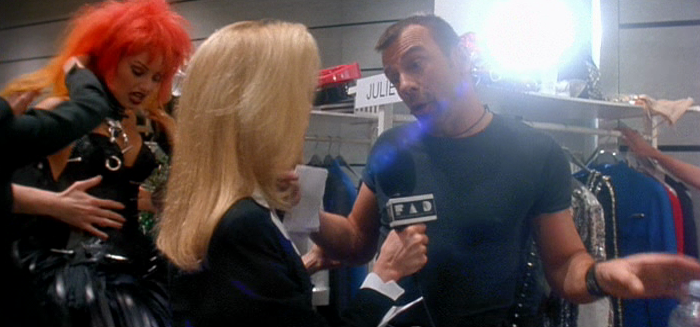

The opportunistic business plan and the long shadows of The Player and Shorts Cuts exacerbated the situation, but I should also make 100% clear: Prêt-à-Porter stinks. And not just from the recurring "joke" of characters stepping in dog shit. It's strange, though: it doesn't stink for failing to pursue artistic aims at which Altman excels. This film is nothing if not "Altman-esque." If anything, the film is an almost embarrassingly unabashed variation on one of Altman's key films, Nashville. The whole idea seems to be "like Nashville, but in the fashion world instead of the country music industry." Like Nashville, it's a sprawling, prickly satire full of larger than life characters of whom Altman delights in undercutting, happily jabbing at their pomposity and pretense. Both stories occur over the span of several days, focused on a central event tangentially tying their large casts together - in Nashville, a political convention in the titular city; in Prêt-à-Porter, fashion week in Paris. In both instances, the cities exist as the center of the universe for a very specific, even exclusionary, culture; in both instances, we enter the story at the moment when both cities and cultures are most the center of their universes. Altman seems none too impressed by the country music industry and fashionistas alike, having fun at the expense of everyone on the social ladder, from the endlessly put-upon nobodies at the bottom to the grandiose bigwigs towering far above them. The odd part of both films, maybe, is that while Altman takes care to knock the wind out of almost anyone on which he sets his sights and provides no convincing "audience surrogate" with whom we can comfortably enter the narrative, he still doesn't seem to hate the worlds he examines, per se. There's a lack of acidity to his cynicism, almost a lightness that suggests he dismisses the idea of taking any of these worlds seriously enough to even really tear into them. These are fatuous people deserving of a fatuous critique. He playfully takes a dump all over them. It might be the highest form of disrespect. Thematic approach aside, the film is constructed in the most stereotypically Altman-esque fashion: a large ensemble that scarcely interacts with each other, loose plotting, meandering shaggy dog sub-plots. Crowded, busy framing combined with a wandering camera and cacophonous, over-lapping dialogue. It even pulls a gag from Tanner '88's repertoire by having an entertainment reporter played by Kim Basinger interview real fashion designers the way Tanner utilized semi-staged footage of real-life politicians. Watching Prêt-à-Porter again for this series, I realized it features Altman's most underrated strength: brilliant opening shots. His camera's virtuosic tracking through The Player's Hollywood backlot might be the most famous example, but I prefer the single-take low-key escape at the beginning of Thieves like Us (and give a special mention to the languid bedroom scene that draws us into The Long Goodbye.) Like these films, Prêt-à-Porter opens with an extended uninterrupted take hinging on a series of slow zooms. Incidentally, it's the best shot and the best part of the movie. We see Marcello Mastrionni shopping for ties in a Dior boutique in an upscale part of town, maybe off of the Place Vendome (or it's Mastrionni, so maybe it’s in Milan.) As Mastrionni purchases the tie, the camera zooms out to reveal it's positioned across the street from the store. The shot follows him as he exits before pulling even wider to reveal that the boutique isn't located in some stylish fashion enclave, but smack in the middle of Moscow. The camera continues to pan, a "The Weinstein Company presents" credit is followed by "directed by Robert Altman" (both written in Cyrillic!) as Mastrionni makes his way across the square in front of Saint Basil's Cathedral. The pan picks up speed, spinning wildly in a circle, the image entirely blurred as credits float upwards on the screen, the names of the huge cast appear on individual fabric swatches. When the credits are complete, the camera stops spinning, finally coming to rest on a scenic view of the Eiffel Tower. I actually made the mistake of getting my hopes up.

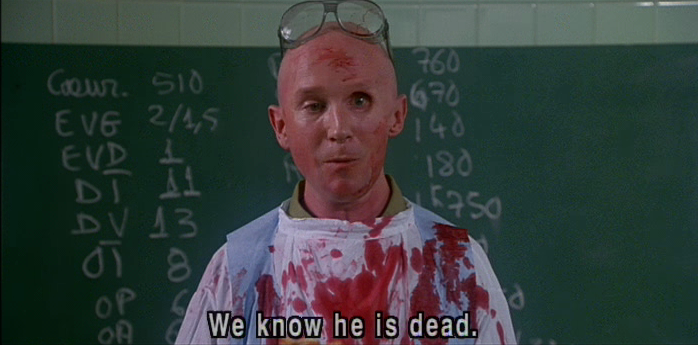

The plot hinges on Mastrionni, the only spine of the film to be found in the story of his former revolutionary attempting to reunite with a lost love played by Sophia Loren. Loren's husband is the head of some fashion organization which oversees fashion week. He chokes on a ham sandwich (his goofy death played Borscht-belt broad) while taking a cab ride with Mastrionni, so everyone thinks the magnate been murdered (possibly because everyone hated him.) The death of this pencil-mustachioed hot-shot throws the naturally chaotic fashion week into even wilder chaos. Theoretically. His death doesn't really seem to affect anything. In fact, nothing that happens in the film really seems to affect anything else, it's the most painfully low-stakes "crazy, chaotic hoopla!" ever committed to celluloid. At first, it seems like it might just be a slow burn, but it never comes close to catching fire – there are dozens of inconsequential plots that resolve with dozens of tiny whimpers, everything from Rupert Everett's affair with two super-model sisters to Kim Basinger's hapless attempts to land a choice interview. It's fun to see Mastrionni and Loren re-enact their memorable sex scene from Yesterday, Today and Tomorrow, but it results in the maddening resolution of their plot: he falls asleep just as she's done her strip-tease and she leaves him a little note that says "my two loves, my two corpses." Ha, ha. I guess. I mean, you did just waste my fucking time so I'm not entirely in the mood to laugh, but thanks for having Loren take her clothes off for us. Even pushing 60, she still looks slammin'. This movie just goes nowhere – it's loaded with interesting actors like Lili Taylor and Lauren Bacall who I can't recall even what their plots were. Taylor's a photographer who took photos of Mastrionni's shoes and tie as he fled the crime scene. Lauren Bacall is a...fashion lady? They're just hanging around and neither of them has anything even remotely interesting or memorable and certainly nothing functional to do. The plot is one big waste of time. That's not true, it's a hundred tiny little wastes of time. There's no drama, no stakes, no one you care about (maybe Mastrionni and Loren, which is why the cutesy fizzle of their story makes you want to throw down your hat in disgust.) Every character is a sharply-etched caricature that never develops beyond that initial broadly drawn impression: trophy wife with pampered dog, too-cool-for-school photographer, bitchy gay NYC/Basquiat-tinged fashion designer, brusque sports reporter, ditsy Southern Belle, suit-wearing business-minded fashion designer, etc. In 30 seconds, Altman makes sure you get the gist of a character and then...lets them lay. There's a couple mild twists, like straight people having homosexual affairs and Danny Aiello's meek small-time reporter turning out to be a cross-dresser, but they're all "wah, wah" style groaners in the vein of Loren and Mastrionni's climactic clunker. Some of these little revelatory gags don't even make any sense – or rather, I can't understand what Altman expects me to make of them.

By far, the most awful subplot of the film concerns Tim Robbins as the aforementioned brusque sports reporter forced to stay in Paris to cover the presumed murder by ham sandwich – it also happens to have the most head-scratching payoff. He gets his orders to stay in town just as he's checking out of his hotel room and it's being handed over to a hapless small-time fashionista played by Julia Roberts. He tries to cancel his checkout and Roberts refuses to let him take his room back because there's no guarantee of her getting another spot in the bustling, over-crowded hotel being invaded by fashion-weekers. Robbins and Roberts race to the room and try to get into it first, both of them refusing to leave after they enter. Put aside that this is re-goddamned-diculous. Or don't: the hotel wouldn't simply let two people claim the same room and duke it out for themselves. Roberts either has a reservation or she doesn't and they either have room to accommodate Robbins or they don't. He doesn't have the right to say "just kidding, I won't check out, I actually own this room technically, it's mine because I had a reservation to stay there until this morning." One of them would get put in another room or Robbins would get booted out on the street, case closed. Don't waste my time with this Mickey Mouse bullshit. But so then the rest of their plot is this: every time Roberts has a drink, she gets so tanked that they end up fucking. They spend all week in the hotel room, doing absolutely nothing other than letting Roberts get inebriated and then getting it on. It's established in his first scene that Robbins has a wife back home, so he's at best a date rapist in an open marriage but he's probably just a regular rapist who is cheating on his wife. The plot is weirdly disconnected from the rest of the movie, even more profoundly than the way in which the other plot strands are disconnected from each other. After the scene in the bustling lobby, they don't interact in any way with any of the other characters and have zero relationship to anything whatsoever. The cynic in me understands that Roberts probably wanted to be involved and for business reasons Altman had to include her. If Weinstein could make him release the film in the U.S. under the title Ready to Wear (because that would somehow be more profitable) then I'm sure he could force the involvement of America's Sweetheart at the height of her fame. Plus it's funny to think of it now, but coming off of The Player and Short Cuts, Tim Robbins was Altman's main man. Having him around probably felt like it would appease the zeitgeist somehow. I mean, what's a late period Altman masterpiece without Tim Robbins? It is nothing, I say. Their disconnected plot that clearly wasn't even shot in Paris along with the rest of the film probably exists as a way of accommodating their busy schedules and getting their name on the poster and in reviews. Their shit stands out as especially pointless and tedious in a film defined by its pointless tedium. But what's the weird climactic gag of this subplot? It's the most unintelligible one in the film. Roberts has been wearing a wine-stained "world’s greatest mom" t-shirt and grey sweatpants the whole movie because she drank too much on the plane and then lost her luggage. When her luggage finally arrives, she gets all gussied up and says to Robbins "Prêt-à-porter, indeed." So...she looks attractive when not wearing a wine-stained t-shirt and sweatpants. That's nice. What am I supposed to get out of this? Sure, it's great to have Julia Roberts saying the title of your film so you can use it in the preview, but did you think any of this through beyond that? And once the title of the film got changed, isn't that not going to make any sense to the mouth-breathers that couldn't be trusted to see a movie with a French title? It's just an amazingly stupid and pointless little subplot clearly motivated by business – you'd have to do something really spectacularly bad to stand out in this film. Congrats, guys - you did it.

As I mentioned, Danny Aiello plays a cross-dresser. The joke is that early on in the film, he finds a pair of panties in his suitcase, immediately calls up Teri Garr and barks into the phone, "You have to be more careful with this stuff!" The implication being that they're having an affair. While Aiello lurks in the background of many scenes, getting ignored by more important industry types, Garr merrily jaunts around Paris,** stopping into those all famous boutiques to buy shoes, dresses and underwear. Oh, ok, she's going to get all sexified for her man. But then Aiello gets dressed up in the shoes, dresses and, presumably, underwear (although fortunately there's no visual confirmation) and the couple goes out to dinner. As I mentioned before, "waaaah, waaaah." I'm describing this plot to lead us into a discussion of the film's weird sexual politics. When they're at the restaurant full of cross-dressers, Lili Taylor saunters in and begins to take photos of the diners. Aiello proceeds to freak the hell out and demand she not photograph him. Taylor isn't malicious, but she doesn't respond to his reasonable demand that she stop taking photos. The whole scene is played like so much of the film as broad comedy, but the whole "joke" of the situation doesn't sit right with me. The idea doesn't extend beyond "he's a cross-dresser, which is funny enough in and of itself, but now he's getting humiliated!" I know a lot has happened in terms of sexual openness even in the past decade so that a film even from the mid-90's is a bit of relic, but I just can't laugh at a cross-dresser (it's his business, some cross-dressing guys are really fucking hot, I'm cool with it either way) and I certainly can't take pleasure in his pathetic flailing humiliation. He's just not a target deserving of scorn or even satirical jabs. The central reversal is too thin to really be comedic (you think he's having an affair, but he's really a cross-dresser!) and the underlying mean-spiritedness isn't warranted. I suppose Altman was an old man by 1994 – being born in 1925, he even comes from a generation before the other Hollywood Film Brat guys – the whole thing just has an air of "uncomfortably racist/homophobic jokes your grandpa tells." I bring it up because the Aiello/Garr sequence isn't an isolated incident: the film is packed with questionable sexual politics that never exactly cross the line into offensively, reactionary bullshit, but come awful goddamned close. If you decide they do cross the line, I won’t argue with you. We can go back to the Robbins/Roberts subplot which is nothing beyond alcohol fueled date-rape played for (nonexistent) laughs. She gets tanked, he fucks her, she tells him she can't make proper decisions when drunk. The story hinges on the fact that she ends up sleeping with guys without real consent because of her drinking problem. Which is, you know, somewhere along the spectrum from hilarious to highly amusing. Rape is always funny, especially the kind of rape that is disputed by sneering meat-heads and results in the most victim-bashing of all forms of rape. Just a good source of chuckles. We can all agree on that.

Possibly worse, though, is the plot following Stephen Rea as the slick, in-demand photographer being courted by the chief editors of the three biggest fashion magazines: Vanity Fair, Stylish Hat Monthly and The Noodler, I believe. All three editorial executives are female and two of the three literally whore themselves out for Rea. Sally Kellerman and Tracy Ullman choose the tactic of trying to fuck Rea into taking their job offers and he uses the opportunity to humiliate them sexually by getting them into compromising situations and then photographing them while naked. I'm not sure her raw sexual power is Ullman's greatest asset, but whatever. Fortunately, we don't see the third editor played by Linda Hunt in any state of undress, she simply gets photographed while groveling on her hands and knees. Not only is photographing someone naked against their will as scummy a move as there is, it is also in many cases a felony. Who knows in fucking France, though. Anyhoo, Altman's sympathies seem to be with Rea and each humiliation sequence is played like it's supposed to be funny. Because the movie is incompetent, these scenes aren't funny, but even more puzzling is that Altman thinks we'll be in total agreement with him that these ladies would most likely be whores in need of merciless sexual debasement. Look Altman, I'm not on the side of the 1% here. I don't like wealthy, pompous magazine editors who oversee industries like fashion that combine the worst aspects of "culturally destructive" and "fatuous." But I'm pretty sure implying they're are all whores who fuck their way to success is counter-productive. And probably factually incorrect, although, who I am, Greydon Carter? What do I know about insider wheeling and dealing? Most rich people I know through my job are borderline asexual and like talking about soccer. Getting back on track, if you want to call this subplot misogynistic garbage, I can't argue against you. Beyond that, since the film has chosen "sexual vagary" as a theme, there are a half-dozen other little bits that ham-fistedly paw at subjects like bisexuality and beauty standards to puzzling effect. Again, I think Altman is just too sex-negative to handle these subjects with intelligence or freakin' maturity. Forest Whittaker and Richard E. Grant play competing designers. Grant is ostensibly straight with a wife/co-designer, but flamboyant, while Whittaker is plain ol' flamboyant with a male assistant/lover. The wacky twist: Grant and Whittaker are having a secret affair, while the assistant and wife/co-designer carry on an affair of their own. Because this is Prêt-à-Porter, the scene where they discover their respective dalliances is contrived, stupid and unfunny – but also because this is Prêt-à-Porter, it feels icky and distasteful, like Altman wants us to think "look at these fucking deviants." Even in the most innocuous setup in the film, the comedy relies on that Altman expects to feel that what we’re seeing is a bit perverted and weird.

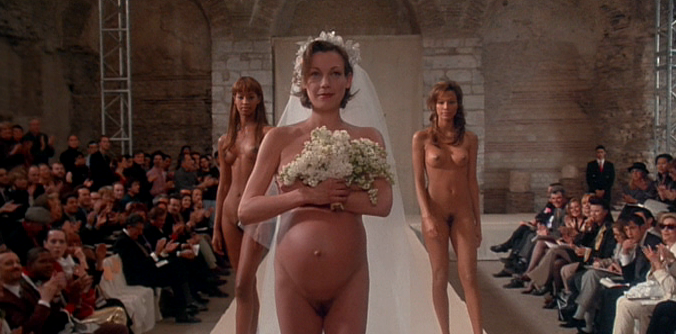

Ultimately, what strikes me in regards to Prêt-à-Porter is just how mysterious it is as to why Altman succeeds or fails as a filmmaker. As I wrote, Prêt-à-Porter is nothing if not Altman-esque – the star-studded ensemble, the cynical satire, the staging and conceptualization. But his talents for pulling this sort of thing off have completely abandoned him. I look at this film and can't figure out why it flops so heavily when incredibly similar films like Nashville or Tanner '88 work. Granted, I think he's had more success when following one or two main characters and more stream-lined plots: in that category you have Thieves like Us, California Split, The Player, 3 Women and The Long Goodbye. Some other good Altman films avoid unrelenting satire as in Short Cuts, The Company or Secret Honor. Some of his very best films even carefully navigate the space between "sprawling" and "focused on a main character or two" as well as leavening their satire with likable characters and charming asides, this is how you end with McCabe & Mrs. Miller and M*A*S*H.*** In his worst movies like Prêt-à-Porter and O.C. and Stiggs, he fails to hold our attention despite the incessant busyness of his narrative structure while utterly failing to provide even a single character about which it is possible to care. His most maddening failure in both films, though, has to be his inability to bring across his ideas. He's satirizing something about the fashion industry in Prêt-à-Porter, but from what perspective and to what effect? Prêt-à-Porter climaxes in a fashion showcase for Anouk Aimee's beleaguered designer. Her no-goodnik son (Rupert Everett) has sold her name to a Texan cowboy boot manufacturer (Lyle Lovett) and generally sold her out in life. She responds by hosting a show in which the models come out wearing nothing at all (gasp.) The crowd bursts into thunderous applause and Kim Basinger throws down her microphone in frustration. She just doesn't get these crazy people! There are two warring ideas brought up by this ending to the film. On the one hand, Amiee gets pushed too far and rebels by showing natural human beauty, literally tossing aside the silly accouterments metaphorically representing the phony culture against which Altman has just spent 2 very long, tedious hours railing. She's our hero! Finally, someone with the guts to cut through the crap and keep it real. On the other hand, this is fucking plot of "The Emperor's New Clothes" where mindless, cowed sheep applaud literally nothing. Aimee's fellow fashion designers are so stupid and pretentious that they will go bananas for the hot new style which isn't even a style. The bile in Altman's satire makes it impossible to accept this as an intentionally ironic thematic counterpoint: he hates these people so much and so gleefully spits all over them for 2 endless hours that it is impossible that he intends for us to take the stance of intellectual neutrality. He clearly wants to pop their bubble, much the way he did with Nashville, but he leaves us on a note that I genuinely can't puzzle out.

I'll finish by saying this: with Prêt-à-Porter, despite his intentions to skewer everyone who passes in front of his camera, Altman comes across as the fool. It's the worst Altman film that could be called exemplary of Altman. The comedy stinks. Anyone who takes pleasure in taking shots at easy targets like, say, Adam Sandler or Norbit, should acknowledge that Prêt-à-Porter fails more miserably at comedy than even the worst brain-dead Seth Rogan fart-swilling comedy. Also, he whiffs at pulling off a withering satire of a bloated, easy target in the much-mocked fashion industry. The film itself undercuts his stance because any time one of the actual designers gets a word in edgewise during one of Basinger's segments, they come across as thoughtful, easy-going and frequently charming. Jean-Paul Gaultier in his brief moments on screen almost entirely subverts the satiric aims of the film by being adorably inclusive, intelligent and unpretentious about his ascendant "freak fetish fashion" aesthetic and his views on how sex and style intersect. I mean, I don't know anything about the man or leather pants, but the dude seems to rule. When a bunch of real-life fashion big-shots are assembled together with the film's fake fashion icons for a group photo, it's hard to sustain any hate for these folks. They just don't seem like they overtly deserve it. As with O.C. and Stiggs, the handicapped-child-bullying homophobes, Altman seems to want us to identify with a perspective that it is all but impossible to respect. It doesn't help that a lot of the actual outrageous fashions at which he seems to be snickering actually look pretty cool. Grant's character stages a drawing-room-themed show and the ornate, lit candles in his models giant powdered wigs are supposed to be silly, but they just look awesome. So much of the fashion on display is impractical and outlandish, but (ironically) these aren't Ready-to-Wear collections, they're high fashion exhibitions centered around aesthetic themes to establish and explicate the tastes and sensibility of the coming fashion season. Yes, wearing candles in your hair would be a dumb thing to do on the subway. But aristocratic-tinged pseudo-drawing-room couture can look pretty awesome if you're even slightly open-minded about the possibilities of fashion and don't automatically think anybody who experiments or pushes the envelope is a pompous boob. If anyone, Altman should be sympathetic to artistic boundary-pushing – the man should just know better. Sure, the real-life Eskimo-themed show skirts offensive racial caricature, but it's several notches below the questionable sexual/political decisions Altman himself has made. And is far less offensive than a single frame of O.C. and Stiggs. Altman's essential tone-deafness in Prêt-à-Porter is inexplicable. His total failure at comedy is inexplicable. His out of touch sexual politics can at least be explained that he was an old man who didn't understand these new-fangled gays and female magazine editors. Obviously though, there's no way to excuse a film like Prêt-à-Porter.

* I once saw Helena Christensen walking down the street in Copenhagen and my first thought genuinely was "goddammit, Ready to Wear sucks."

** I should mention that she gives an extremely weird performance where she's overplaying her happiness, but almost like a mime. It makes you wonder just exactly what Altman instructed her to do in these scenes. For how simple what she’s asked to do is, she sure does make it baffling.

*** If you actually like Gosford Park and Prairie Home Companion, this is the category in which they most comfortably fit.

Related Articles

home about contact us featured writings years in review film productions

All rights reserved The Pink Smoke © 2011