ray bradbury

WEEK

john b. cribbs

All visible things are emblems; what thou seest is not there on its own account; strictly taken, is not there at all: Matter exists only spiritually, and to represent some Idea, and body it forth. Hence Clothes, as despicable as we think them, are so unspeakably significant. Clothes, from the King's mantle downwards, are emblematic, not of want only, but of a manifold cunning Victory over Want. On the other hand, all Emblematic things are properly Clothes, thought-woven or hand-woven: must not the Imagination weave Garments, visible Bodies, wherein the else invisible creations and inspirations of our Reason are, like Spirits, revealed, and first become all-powerful; the rather if, as we often see, the Hand too aid her, and (by wool Clothes or otherwise) reveal such even to the outward eye? Men are properly said to be clothed with Authority, clothed with Beauty, with Curses, and the like. Nay, if you consider it, what is Man himself, and his whole terrestrial Life, but an Emblem; a Clothing or visible Garment for that divine ME of his, cast hither, like a light-particle, down from Heaven? Thus is he said also to be clothed with a Body.

- Thomas Carlyle, Sartor Resartus.

The fearful Unbelief is unbelief in yourself.

- Thomas Carlyle, Sartor Resartus.

THE WONDERFUL ICE CREAM SUIT

stuart gordon, 1998.

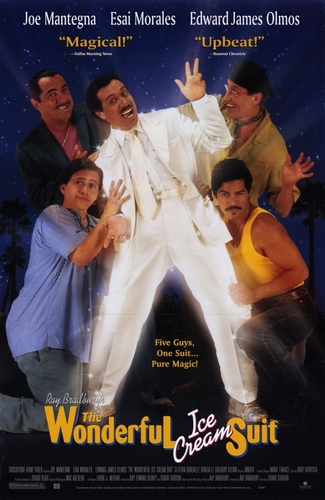

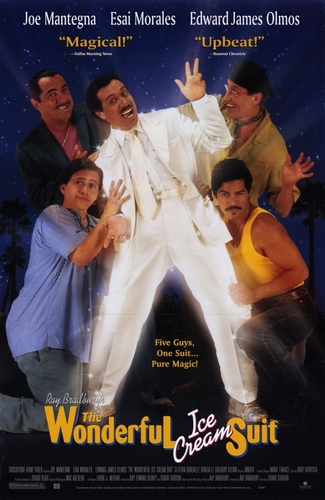

Last summer, I started a series on the Pink Smoke in honor of Ray Bradbury's 90th year on planet Earth. Although it's being published much later than I had hoped, this is what it's all been leading up to: my revisiting of a truly exceptional film that I earnestly hope more people begin to discover and re-discover over the next few years. It's a movie about one suit that five people buy together to share, a suit that over a single incredible night allows each of them to shine brighter than they ever thought possible. Like the suit, the movie brings out the best in the considerable talent of those involved in its production and, like the suit, makes for that rare communal experience that can be passed on and enjoyed from one person to another - if the viewer can check his cynicism at the door for the modest 77 minutes it takes to be charmed by this film, it will work the same magic on him. Bradbury's story is such that the film seems constructed from the same stitch and fabric as its eponymous outfit, magically bespoke to whoever might be "wearing" it at the time. At its heart it is essential Bradbury: a story about everyday people who find themselves in a fantastic situation that nevertheless brings out their most pointedly human characteristics. But it's also about a specific group of people at a certain time in their lives, and that's what makes their adventure so remarkable.

The origin of the film goes back to 1974 when Stuart Gordon, founding artistic director of Chicago's Organic Theater Company*, was looking for a follow-up to the group's premiere production of David Mamet's Sexual Perversity in Chicago, a huge success for the company as well as a breakout for its playwright.

The origin of the film goes back to 1974 when Stuart Gordon, founding artistic director of Chicago's Organic Theater Company*, was looking for a follow-up to the group's premiere production of David Mamet's Sexual Perversity in Chicago, a huge success for the company as well as a breakout for its playwright.

Gordon's brother brought to his attention a quirky comedy called The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit by famed science fiction writer Ray Bradbury. Bradbury had already produced the play through his own L.A.-based Pandemonium Theater Company: they had taken it to New York, opened Off Off Broadway and closed the same week due to a newspaper strike that limited publicity. Gordon instantly recognized the appeal in the play's simple story of five down-and-out Latinos living in Los Angeles whose lives are marvelously changed by a vanilla white suit they purchase together and take turns wearing. Organic's staging of Ice Cream Suit, with a cast that included young Joe Mantegna, Dennis Franz and Bruce (later Meshach) Taylor, was another hit for the company and they ended up touring the show. Bradbury attended a performance at UCLA Berkeley and, delighted by the uninhibited zest and energy with which his work had been presented, climbed on stage afterwards to say hello.

"He said, 'I want to wear the suit.'" Gordon remembers. "We didn't believe him, then all of a sudden he starts taking off his clothes! All the guys gathered around him, like in the play, to try and help him in terms of modesty. He literally stripped down to his boxers and put on the suit. This was the first time we were meeting him! And once you've seen someone in their boxer shorts, you're friends forever."

Friendship is the central concern of the story, which came from the writer's own relationship with Mexican-American immigrants he lived among as a young man making ends meet from a tenement at the corner of Figueroa Street and Temple in the Boyle Heights district of East Los Angeles. "I saw my friends coming and going from Mexico City, Laredo, and Juarez," Bradbury explained. "Their poverty and mine were identical. I saw them share clothes, as I did with my father and brother**... I knew what a suit could mean to them." The young writer would also watch the Latina women "on the porches after a big party, like Cinco de Mayo, throwing their dresses off the tenement to other women down below. So the dresses the women used during Cinco de Mayo became the clothing the young women who owned no dresses used for the rest of the year." Bradbury turned these experiences into stories like "En La Noche" and "I See You Never," both included in his fantastic short story collection The Golden Apples of the Sun, but most extensively into "The Magic White Suit," originally published in The Saturday Evening Post in 1957.

"What would inspire him to write something like this? Why would you want to write a story about these people?" actor Clifton Collins Jr. wanted to know, and asked the author during the movie's production. Bradbury's answer: "Well, I hung out with them!" He felt an affinity towards the men and women who inspired "Suit," borrowed their names and transferred their larger-than-life personalities into the five characters who find each other in the story: lovestruck, luckless Martinez; shifty opportunist Gomez; handsome street guitarist Dominguez; frustrated poet and thinker Villanazul; impulsive, uncontrollable Vamenos. Their lives are a reflection of the kind of noble poverty Bradbury saw all around him, with people uniting to help each other make ends meet. "They would all share their clothes, which was very common for any family who's struggling," says Collins. "But these stories came from his personal memories, which made it that much more special." Just as he had once looked at a wrecked roller coaster on the beach and seen the sad remains of an ancient dinosaur, Bradbury took those memories and reflections and added a spectacular symbol of that shared desire to survive and succeed.

The story, retitled "The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit," was adapted for a 1958 episode of the anthology series "Rendezvous" before Bradbury reimagined it as a play; there would later be a musical version. Remarkably, the first person to show interest in bringing the story to the big screen was Federico Fellini. He and Bradbury were mutual fans of each other's work and Fellini must have felt a fantasist's bond: when they first met, he embraced the writer and proclaimed "My twin, my twin!" They became great friends but the Ice Cream Suit project, which Fellini intended to relocate to Rome with poverty-stricken Italian protagonists*** rather than Latinos, never came to be. Instead Gordon, who had kept in touch with Bradbury since the writer's impromptu disrobing at the UCLA theater, contacted him in the mid-90's about collaborating on a film version. Since his days at the Organic theater, Gordon had entered into a distinguished and prolific movie career directing a series of excellent adaptations of H.P. Lovecraft (Re-Animator, From Beyond) and Edgar Allan Poe (The Pit and the Pendulum) for Charles Band's production company. After his family-oriented screenplay Teenie Weenies became the 1989 hit Honey I Shrunk the Kids, Gordon was given an office at Walt Disney Studios, which is where he opted to pitch the project with Bradbury. The author also had a relationship with the company from the early 80's, when he was hired as an imagineer to help design Spaceship Earth, the 18-story geodesic sphere that doubles as the centerpiece and an exhibition at Walt Disney World's Epcot Center. "We went to the head of production at Disney," Gordon recalls, "and Ray turned up wearing an ice cream suit. I'm thinking, we can't lose here. Here's Bradbury himself, wearing a white suit - this is going to happen."

But it didn't; a few days later Gordon was informed that Disney would be passing on the project. "The reason, they said, was that the movie was too small, the idea was too small for a film. So I called up Ray to tell him the bad news, and he was disappointed. Then he said, 'Roy Disney is a big fan of the play, he's come to see it many times.' I said, 'Roy Disney? THE Roy Disney?'" Disney, nephew of Walt and longtime senior executive for The Walt Disney Company, had fended off hostile takeovers and weathered two decade's worth of corporate civil war within the company before taking over as head of the animation department. He greenlit Gordon and Bradbury's proposal on the spot, and for a year Ice Cream Suit was developed as an animated film with character sketches and background drawings**** being created from Bradbury's script. Eventually the idea to animate the story was also axed, but Roy Disney ensured that a live action version be produced through Touchstone Pictures, which he was also overseeing at the time. However the stipulation from the reluctant production office was that the budget not exceed $5 million, and that the movie would be released direct-to-video, a marketing tactic the Disney Company had only recently started (coincidentally the first live action title Disney introduced to this new distribution practice was Honey We Shrunk Ourselves, the second sequel to the hit film Gordon had brought to the studio - Ice Cream Suit would be its first non-sequel to go straight to video.)

Gordon was willing to work under these conditions, considering the amount of freedom he was given and the people he was working with. Joe Mantegna returned to the role of wily Gomez, the same part he had played in the Organic Theater's production 25 years earlier. Collins, who had co-starred in Gordon's futuristic action thriller Fortress, took the role of down-and-out Martinez. Esai Morales, the handsome Puerto Rican who turned heads as Bob Valenzuela in La Bamba 10 years earlier, and Gregory Sierra, known for co-starring on "Barney Miller" and "Sanford and Son"*** **, were cast as guitarist Dominguez and poet Villanazul, respectively. The part of Villanazul was originally offered to Edward James Olmos, but the Academy Award nominee had a different suggestion: that he play against type as wild vagrant Vamenos. "Stuart was going to go after a comedian," Olmos remembers. "He was going after Paul Rodriguez for the role. He told me he wanted me to play the poet, and I said 'I would love to and I'll do anything I can to help, but could I ask you something? Can I play Vamenos?' And he took a beat, a long one, and said, 'Well... that's different.'"

"I couldn't quite get my head around that idea," Gordon admits. "Everything I'd seen him in, he'd been so serious! I said, 'I don't know Eddie, I've never seen you be funny.' He said, 'Watch this,' and he starting acting out some of the lines, and he was hilarious. It was like working with Charlie Chaplin."

Another delight for Gordon and the crew was having Bradbury, who had written the screenplay (to date, the only adaptation of his own work written for a completed feature film), present on set every day of production. "I just wanted to sit next to him," Collins says. "Just wanted to hear him talk, just wanted to ask him questions. We'd all crowd around him; anything that came out of the man's mouth you just wanted to sit and listen." Mantegna reflects on the original Chicago production as "a major touchstone for my career," but found the filming of the movie even more enriching, having grown up a Bradbury fan. "My idol as an author had now become a friend and an associate," he told Sam Weller for his Bradbury biography. "Of all the joys my career has afforded me, my relation to Ray Bradbury will stand as one of the most shining aspects of it. "It was the best thing in the world," Olmos attests. "I love that man. A truly gifted genius."Bradbury himself was happy with what he saw, telling interviewer Sandy Hill in 1997, "The filming has gone beautifully. I'm very happy about it. For the first time in my life they are filming exactly every word and every scene that I wrote. Unbelievable."

The film opens with a catchy number sung in both English and Spanish by Nydia Rojas, set to a gorgeous title sequence designed by Robert Dawson, who had done the title sequences for Gordon's early films and has since gone on to become one of the most famous title designers in Hollywood. Dawson hired artist Aleksandra Korejwo, who used salt animation to create a colorful wave of painted particles that look like sand being blown into semblances of Diego Rivera-like murals. Gordon was particularly impressed by Korejwo's work. "It sounds like something Bradbury would dream up - she would move the salt around with a feather, I think it was a condor feather. And it had to be that kind of feather, that strong a feather. She said she used to go to the zoo in Warsaw and get condor feathers from the zookeeper, that those were the best feathers to use!" At the film's Sundance screening, the credits were given a standing ovation and Korejwo's sequence was subsequently nominated for the International Animation Film Association's Annie Award (imdb doesn't list a winner among the nominees - maybe they forgot to give out the award?)

The first shots of the film glide slowly across spillways and interchanges and over buildings until we reach Boyle Heights, dwarfed by the towering architecture of West L.A. across the river. Gordon intentionally evokes the opening shots of West Side Story, although the Latinos living here are less the dance-prone Puerto Rican street gang of Robert Wise's New York and more the big hat-wearing, guitar-noodling corner dwellers with stripes down the side of their pants. "We were right there in Mariachi Plaza," says Gordon. "There were taco trucks, mariachis were still there. It felt like you were living in the area where that story took place." In fact these were the exact same streets a twenty-something Bradbury shared with the people who inspired the story. Their five cinematic equivalents are jobless and on the brink of eviction, so poor they have to cheat a scale to weigh themselves in a pool hall. As it turns out, they're all roughly the same weight and their measurements miraculously match: each a variant of the same hopeful dreamer. They each pull their last $20 to buy a single suit - "The only suit in the world!" - white as vanilla ice cream, to wear around the highly populated streets of the neighborhood in hopes of gaining some of the visibility that's been absent from their lives.

They purchase the suit from two nervous tailors in a shop, played by Sid Caesar and Howard Morris,*** *** legendary veterans of "Your Show of Shows," known to any household with a TV in it in the 50's - the same decade as Bradbury's story was originally published. Their presence on set was another highlight for Gordon: "They were like the greatest comedians of all time. I tried to shoot (Caesar) in long takes so he could do whatever he wanted to do, and every single take was different; every take he'd come up with new lines. You can see in some of the takes that the actors are laughing. Ray was kind of protective of his dialogue, so when Sid was doing his takes I would kind of turn to Bradbury and say 'Is this ok?' and he would be laughing so hard he couldn't even speak." The duo perfectly embody the jittery salesmen from Bradbury's story, the unwitting genies who bestow the team with their magical garment. Particularly sweet is a moment where Morris worries that they're setting a dangerous precedent from a business end by selling one suit to five people, to which Caesar responds, "But did you ever see a hundred dollar suit make so many people so happy?" Reflecting upon the beaming faces of the five friends, he confides to his partner, "You know what? That's one hell of a suit!"

Another notable cameo appearance is Pedro Gonzalez-Gonzalez in the final role of his 45-year film and television career as a comedic character actor.**** *** Pedro had first came to notice in 1950 as a contestant on Groucho Marx's "You Bet Your Life," on which he shared banter with the famed comedian like the following:

Groucho: "If we got together as an act, what would it be called?"

Pedro: "Gonzalez-Gonzalez and Marx."

Groucho: "Do you believe that? Two men in the act, and I get third billing!"

His appearance on the show brought him to the attention of John Wayne, who signed the diminutive comedian to a contract with his production company, leading to a string of half a dozen stock player parts in films starring the Duke, most famously as innkeeper Carlos Robante in Rio Bravo. In one of his greatest film moments, Pedro played his pants like a musical instrument. Although the roles relied on him for unrestrained Latin caricature comedy relief, Pedro's talent was such that he was able to draw humor not simply from being a stereotype but from bringing the lighter side of a largely misrepresented culture to the comedy. The characters he played weren't so much representative of his heritage as they were a response to the way American audiences envisioned Latino citizens. That's what makes his brief appearance in Ice Cream Suit, as Martinez's landlord, so conceptually perfect, because the humor of the film can be defined in the same way. Bradbury has a genuine love for the five heroes and the community they belong to, his characters' frantic mannerisms (exemplified by Olmos' exaggerated body language), tendency to fall back on goofy Spanglish (Villanazul referring to Vamenos as "Stinko!") and use of Mexican colloquialisms (Gomez's explanation of "Ay chihuahua!" after being punched in the face) all act as endearing tributes to Pedro, whose performances have been an obvious influence on performers like Cheech Marin (who remembers Pedro as "the first Mexican I ever saw on TV"), Trinidad Silva, George Lopez - even the evolution of Looney Tunes staple Speedy Gonzales.

Pedro was also an inspiration to his grandson: Clifton Collins, Jr. "My grampa was just a funny, brilliant guy. For improv, for dialogue, for physical comedy. Really just hanging out with him was enough to draw on." Out of respect for his grandfather, Collins billed himself as "Clifton Gonzalez-Gonzalez" for much of the first leg of his career. Perhaps appearing along side his legendary abuelo was enough for him to confidently shed this magic suit of a moniker - after Ice Cream Suit, he would go on to celebrated roles in films like Traffic and Capote under his original name. In 2008 he presented his grandfather a posthumous star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame, which was placed a few feet from John Wayne's. In Pedro's obituary in the San Jose Mercury News, Olmos called him an inspiration to all Latino actors.

Because they can't wait for their own individual days to use the suit, the gang decide upon returning to Gomez's apartment to each go out for an hour that evening clad in the blindingly white ensemble. Dominguez goes first ("How clean it sounds!" they marvel as he puts it on), and stirs the entire neighborhood with a bouncy musical number, causing the crowd to ¡Muevete! (loosely translated, "move to a rockin' song.") The song, powered by the suit, motivates the women of the building to escape their shackles: a housewife drops the dirty dishes and sneaks out without her beer-sipping, TV-hypnotized husband noticing, a young woman rejects the flowers by a parents-approved suitor, a teenager escapes a boring evening with grandma (at the same time, granny gets in on the action too.) There's a little moment, so subtle it's easy to miss, where a hint of rivalry passes between two of the women as Dominguez serenades them, but it's mutually extinguished so they can continue dancing with the group - the suit maintains the atmosphere of excitement and community. Esai Morales, whose singing part was dubbed in La Bamba, was happy to be doing his own work here and does a fantastic job mastering the rollicking vocals and choreographer Miranda Garrison's lively shuffle steps.

Following a soft fade to white that marks the transition between suit wearers we have Villanazul, the sight of the suit enough to dazzle a crowd who hang on every word of a poetic speech he gives imploring the community of East Los Angeles to "cross that river" and make themselves heard in West Los Angeles. It's hard not to consider this the weakest part of the film, it's so carefully paced after the big musical number and the speech - stripped of any clear political motivation - so ambiguous (the crowd also applauds before he says anything, a funny moment but also easy to misconstrue as a hypnotized mob applauding anything somebody wearing the suit should happen to say and somewhat undermining the speech itself**** ****.) Not knowing where Villanazul is coming from or what his passions are specifically makes it hard to engage what he's saying, even though what he says is eloquently written by Bradbury, well delivered by Sierra and creatively shot by Gordon, who intercuts a confident Villanazul speaking directly to camera while leading a parade over the Figueroa Bridge, "'cross that river," on a bright Los Angeles day. In fact a frequent criticism I've found of the film and the play is the lack of backstory for all five characters beyond their common motivation: to be seen and heard for once in their lives. Their generic Hispanic names - only Martinez lets slip his first name, and it's "Jose" - could also be considered superficial character appellations. But such naysayers seem to misunderstand what Bradbury had in mind for his five heroes: that the suit would bring out what their introverted personalities had kept dormant. It's significant that Martinez only reveals his (admittedly common) first name after the suit has helped make him visible to the beautiful neighbor whose attention he's been pining for, and that she repeats it back to him! And that's exactly how Villanazul's speech becomes relevant to the larger context of the story: he has the poetry to find the words (the other guys keep asking him to "say that again!" after he makes a lyrical statement) but through him the suit states its purpose, to bring out each member of the gang's individuality in order for them to come together as a community, so that "a thousand, a million Gomezes, Martinezes, Dominguezes march off in white armor way down the line, reflected again and again: indominable. Forever!"

So the suit affords them confidence, but each has an accessory of his own that goes with it: Dominguez has his guitar, Villanazul keeps his trademark glasses and barret, Gomez his toothpick (a symbol of his craftiness and desired business-savvy), even a cleaned-up Vamenos maintains his dirty sneakers. Martinez doesn't have an instrument, a barret or even a mustache to go with the garment, but learns when he dons the suit that he, like his new friends, has had his own assessory all along. Secure in his bright finery, he rushes to the window of a beautiful young woman - Celia Obregon - who has never noticed him even when he's waving frantically to gain her attention. This seeming rejection has left the man with some serious self image issues ("I haven't been beautiful in years," he states dejectedly) and he despairs yet again when Celia moves back into her apartment, apparently not noticing him in the suit. But she returns with something in her hand: a pair of glasses. With these she sees him clearly, having caught a glimmer of "whiteness" from her limited field of vision - not, she insists, the suit but Martinez's smile and his "so many" teeth. It is Martinez she's noticed after all, and Bradbury has established that it really is the man wearing the suit and not the other way around. Collins plays the piece perfectly, his charmingly exaggerated pining recalls a lovestruck Buster Keaton and the very lovely, subtle scene easily stands along side balcony flirtations from plays-turned-movies Romeo and Juliet and Cyrano de Bergerac that influenced the unashamedly sweet nature of Martinez's wooing.

Next up is Gomez, who has been palming a ticket to El Paso all evening. His old friends Dominguez and Villanazul have suspected the fast-talking swindler - whose ventures such as the Everybody Wins! Punchboard Lotteries and United Chili Con Carne and Frijole Company have been money-losing debacles - of taking off with the suit, and their fears are confirmed as Gomez prepares to board the bus. He's torn by guilt, and ultimately finds himself compelled by the suit's influence towards friendship and community to return to the apartment. Most overwhelming in his decision to ignore the advantages a suit should supply in the real world (opportunity, advancement, change) is a painted mural of Latino faces that transform into likenesses of the four men he's about to betray; the cultural implications of the artwork, suggesting that he is simultaneously betraying his own people, provide additional symbolism. This is another extraordinary moment that must be unique to the film (I can't see how they would achieve it onstage, although I wouldn't be surprised to hear that Gordon found a way) which once again states the true nature of the suit in bringing these people together. When Villanazul changes into the suit and wants to see how he looks (Gomez reveals he was forced to sell his mirror, a throwaway gag that gets me everytime), he stands the other four men in front of him so "I can see myself in your eyes - in your faces!" Martinez returns from his successful meeting with Celia Obregon crowing like a rooster, spinning, drunk "with life," and shares with the others the pure ecstasy of being together, changing clothes, dancing. In the final scene he reveals that the night has made him feel like "Gomez, Dominguez, Villanazul y Vamenos - I am everyone!" When Vamenos screws up later in the film, his only concern is that the others don't kick him out of the gang - although he cares about the suit, it's the unity the five of them have established over the course of a couple hours that really matters to him. The suit wasn't made for one person, Gomez realizes as he stands in line to board the bus to El Paso: it comes from the need to be part of a group or a family, something recognizable in all of them and all of us.

Most unrecognizable of the cast is Olmos, whose Vamenos is so dirt-encrusted he looks as if he's been down a mine shaft for the last ten years (the result of eight hours a day between the hair, wardrobe and makeup departments.) "There are certain layers, even of poverty," says Olmos. "Some people hit poverty much lower than others. I said, 'We need him in the dumpster.' So I knew that we were starting at the very very bottom rung, and that this guy had to be a person who was very much at peace, very much in tune with where he was. He wasn't feeling sorry for himself, he didn't think he was something that he wasn't...he was what he was, and never expected to change." The actor's goal was to create a character who "walked the streets very boldly," not concerned with how people saw him, an objective Olmos reached by scrounging trash cans in the area in character, covered head-to-toe in grime. "I was looking at the people looking at me, and I could see they would look away like they hadn't seen me. And I could see it was working. Everybody was looking at me when I wasn't looking at them, but as soon as I was looking they'd look away." The transformation was so convincing, when Olmos showed up in full costume for rehearsal at the Wilshire Hotel, somebody called the cops ("When they found out it was a movie and I was playing a character, they started laughing," recounts Olmos.)

Throughout the movie the other characters turn away from Vamenos in disgust, try to avoid his musky odor and fret over his reckless lifestyle, especially when it comes his turn to wear the suit. ("I had sprayed almost a whole bottle of Old Spice cologne on me," Olmos remembers. "They could smell me coming 10 to 15 feet away. It was a sweet smell, but I told the guys that whenever they smelled me they should turn away as if it were disgusting.") When it inevitably comes, they demand he take a bath, something he hasn't done since 1989. This leads to the film's funniest scene and the most literal transformation among the characters, as a freshly-bathed Vamenos is given a set of rules to follow for the preservation of their shared suit, all of which he breaks by heading directly to the Red Rooster Cafe and Cocktail Lounge, where there are fights "on the TV and in front of it."

Vamenos is an amazing achievement, one who belongs to the great vagrants of film history, most notably Michel Simon in Boudu Saved from Drowning, whose title tramp is also bathed, shaved and placed in a suit. Gordon's Chaplin comparison isn't far off the mark either, as Vamenos is equally good-natured as he is prone to Rabelasian abandon. His sweet nature is something Vamenos shares with the silent screen legend's Little Fellow, in spite of his proclivity for wine and women (which I guess you could say he shares with the screen legend himself.) Olmos' performance is amazing of course, but what really makes the character work is the way the actor's transformation ties into the themes of the film and parallels the rowdy vagrant's journey. According to Olmos, when the cast and crew saw the completed effect, they couldn't believe it was him. "Even Stuart was a little taken aback, he was just like 'Wow, this is really radical! I can't even see you!' I said, That's exactly the idea. You will not be able to see me if you don't know it's me. You see the picture more than once and you'll notice who I am; you'll see my face as a character because I'm not trying to hide it. But, when you don't know that it's me in there, when you have to wait for me to get all cleaned up to meet me - you know, people had no idea who the actor was." Perception is everything, and Vamenos becomes Carlyle's living "visible garment," an emblem - like the suit - to represent "a manifold cunning Victory over Want." After he's had a bath, been clean shaven and placed in the immaculate ice cream suit the audience can tell it's Edward James Olmos, but the filth that's been washed from his flesh is as much a piece of clothing as the magical set he's placed into: all the change does is free Vamenos to be even more flamboyant and clownish, to prove that he's the same man. The orphic outfit doesn't bring him girls or a group of eager listeners - it simply allows him to be more Vamenos than he ever thought possible.

Bradbury's story is magical, and the movie creates a subtle feeling of magic all its own. We see a character on the street and a second later he's upstairs. The gang is arguing whether or not to go after Vamenos in the suit, and we instantly cut to a different location where the dialogue continues uninterrupted, as if they've been magically transported to their destination through the unspoken understanding of the conversation. Villanazul couldn't possibly walk halfway across the Figueroa Bridge and back in one hour any more than he could be speaking directly to the audience and leading his parade in the daylight hours, but it all fits in with the limitless possibilites of Bradbury's world. Dominguez's musical number, Vamenos' abrupt physical transformation, Gomez's discovery of Martinez on the streets...it would all be unbelievable if Gordon didn't do such a fantastic job keeping things consistently...fantastic. It comes from a kind of cinematic magical realism (since used to less successful effect in movies like Big Fish and The Life Aquatic) not far from the literary counterpart. Bradbury's story does have the same feeling as a short work by writers like Gabriel García Márquez or Julio Cortázar. In fact, a good example of what a suit and its shared experiences mean to the man who owns it can be found in a segment from Peter Carey's epic work of magical realism Illywhacker: Two friends have shared a suit through their years of struggle. Once their fortunes improve, one gives the suit away to an impoverished shoelace seller. His friend Wysbraum is aghast - "You have given away my history!" The man reconstructs the suit, having "lovingly counterfeited the tear Wysbraum had made falling off the cable car twenty years before" and replacing all the "olfactory richness and squalor of years of split meals" so that Wysbraum is able to accept it emotionally as "a perfect copy." His attachment to the suit is how it reflects his own struggle to become the man he is, as the dresses thrown to the young women during festivities in Bradbury's old Boyle Heights neighborhood reflect the person they could become.

Surfaces and appearances pop up constantly in Bradbury's work and the films they birth: the aliens from It Came from Outer Space with their "human suits," the Illustrated Man's clothing of tattoos that tell his story, the magical shapeshifting into an older or younger version of oneself in Something Wicked This Way Comes. But the suit - a white obsession like Moby Dick - has to be among his greatest creations, as inspired a wearable centerpiece to a modern fable as Red Riding Hood's cloak or Cinderella's slipper. To take something as comforming and symbolically spirit-crushing as a suit (just think about those who wear suits in a modern fable like, say, The Matrix) and make it magical - well, that's just Bradbury. He borrows from Carlyle the idea that the bodies inside the clothes are the truly divine vessels, something Olmos agrees with: "Mentally they were able to do things they normally wouldn't be able to do, not because it was magic but because they were given an opportunity to FEEL that they could. And that's exactly what the reality was. They put the magic in the suit. The suit was magical because of the fact that they believed that it was. But the magic came from them." Again, this is most apparent when Celia is drawn to Martinez by the whiteness of his smile. In the short story, Celia specifically tells him "You do not need the suit. If it were just the suit, anyone would be fine in it. But no, I watched. I saw many men in that suit, all different, this night. So again I say, you do not need...the suit." (Martinez then tells her that he will need the suit for a while, a month or a few weeks, until he grows out of his youthful insecurities. She understands.) The magic of the suit is supplied by the person within - the suit itself doesn't make Martinez attractive, Villanazul a better speaker, doesn't make Dominguez a better guitarist. "It's like Dumbo's feather - he doesn't really need it," says Gordon. "The thing that's also kind of beautiful about the story is that it's left open-ended. Is it a magic suit or isn't it? We don't know. But magical things happen when they're wearing it."

The film is an excellent companion piece to Alexander Mackendrick's 1951 movie The Man in the White Suit, another charming underrated classic that's equal parts comedy, science fiction, romance and social drama (it's also adapted by a writer from his own play.) In that Ealing fable, idealist inventor Alec Guinness adorns himself in his own accomplishment: a bright white suit made from material that repels dirt and will never wear out. The woman he's been trying to impress laughs when she sees him, exclaiming "It looks like the suit is wearing YOU!" which is appropriate enough - the idea behind the film is that nobody is necessarily defined by what they do (or, wear) but who they are underneath the unbreakable material. Guinness learns the suit doesn't define him any more than it symbolizes industrial ruin for the capitalists and loss of jobs for the labor union, even though all representatives of both parties can see in the London fog is the glaring luster of the suit that spells their doom. Mackendrick's movie, although tonally and stylistically miles away from Gordon's, has the same message at heart: clothes don't define the man - man defines the clothes. (I will add that it's kind of incredible how Gordon and his frequent cinematographer Mac Ahlberg managed to do as good a job making the suit shine as effulgently in color as Mackendrick and Douglas Slocombe did in black & white. I don't know how they did that.***** ****)

Despite positive receptions at Sundance and the Austin Film Festival, the film was released, as planned, unceremoniously straight to video in 1999. "I think part of it was that Disney just didn't know what they had there," says Gordon. "I don't know what happened, it's almost like they buried it." The film was nominated for Fantasporto's International Fantasy Film Award***** ***** for Best Film, a prize that has gone to such worthy films as Braindead and A Tale of Two Sisters and such less-worthy films as Monkey Shines, Black Rainbow and Piranha Part Two: The Spawning (Ice Cream Suit lost to Louis Morneau's Retroactive, starring James Belushi and Sharon Whirry...I don't know.) Although its video release received a colorfully favorable review from Peter Nichols in the New York Times, it still remains fairly difficult to track down, its official DVD release having already gone out-of-print. "Michael Eisner didn't want to make the movie. He appreciated that it was a labor of love, but never really understood the film," Olmos laments, although he adds optimistically, "I think it has more of an audience today than back then, and I think it's going to keep growing." "I've asked the Disney people to re-release it to theaters," says Bradbury. "I wish they would."

When asked recently about the films made from his work, Bradbury stated "The Wonderful Ice Cream Suit is my favorite. The director followed my script. It's that simple. It's a beautiful film." "It was wonderful," Gordon agrees, "because they let us do what we wanted to do and use Ray's script. It was actually the best experience I've ever had making a movie." Olmos summed it up for Peter Nichols by simply stating that it was "the most fun I've ever had on a movie" and Collins concurs, saying "It was a fun one - the music, the culture, the food, where we shot...It's just a very special little film."

Is it actually better that the film remains obscure? Does the nature of the film not lend itself to discovery, for one person to find it and pass it on to a friend like the suit itself? "If we ever get rich," Martinez muses in the film's final moments, "it'll be kinda sad." He knows that the thrill of friendship and anticipation for a bright future would be gone; the suit would lose its power. "Yeah," Gomez acknowledges. "It'll never be the same...after that." Nothing lasts forever, but the chance to enjoy the suit - or the film, or the work of Ray Bradbury - is something to be grateful for. The film ends with a visual directly from Bradbury's story: "the neon lights from nearby buildings flicked on, flicked off, flicked on, flicked off, revealing and then vanishing, revealing and then vanishing, their wonderful white vanilla ice cream suit."

This is a film that means a lot to me personally - one of those movies that came at exactly the right time in my life. I was living in a tiny one-bedroom apartment in White Plains, no job, no car, no money. For lunch I would go down to the galleria and walk back and forth among the food court workers who were handing out free samples until they caught on to me and refused to give me any more toothpicks with bits of teriyaki chicken on the end. And I had maybe two shirts and one pair of pants (we won't go into the amount of underwear I had on hand.) I would sit - I guess "loiter" is the right term - at the Metro North station spying on people as they commuted to the city, wondering where they were going in such spiffy suits. Everyone on the planet seemed to have things figured out except me, and I was more than a little depressed for long stretches of time. My one outlet was the video store across the street, which put new movies on the shelf every Tuesday. One Tuesday this video was on the shelf. Wonderful Ice Cream Suit was, for me, what the suit was for the characters in the film: a chance to learn something new about myself and the world around me.

MANY THANKS to Stuart Gordon, Clifton Collins Jr. and Edward James Olmos for taking time to talk to me about this unique film, and to Kim Callahan and Brad Pence at Affirmative Entertainment and Perla Aboulache at Olmos Productions for arranging interviews.

~ 2011 ~

* "Venturesome, innovative, energetic, improvisational, and always on the edge of disaster or triumph, (the Organic Theater Company) was a small but powerful and influential force in fostering the talent and shaping the personality of the city’s theater scene. It produced more than a few duds, but it also presented a handful of Chicago-born masterworks that were both supremely of the moment and way ahead of their time." - Richard Christiansen, A Theater of Our Own: A History and Memoir of 1,001 Nights in Chicago.

** Bradbury elaborates: "I remember graduating from Los Angeles High School wearing a hand-me-down suit in which one of my uncles had been killed by a holdup man. There was a bullet hole in the front and one going out the back of the suit. My family was on government relief when I graduated. What else, but wear the suit, bullet holes and all?"

*** An Italian comedy-social drama with fantastic elements featuring dirt poor protagonists? Makes me think of Vittorio De Sica's equally wonderful Miracle in Milan.

**** I tried so hard to find out if any of this pre-production work still existed, going back and forth over the phone with the archives & research people at Disney's animation studio. The most-quoted reason for their reluctance to help me was "we usually don't help people outside of Disney." Too bad - I'd love to see some of those character sketches.

*** ** Sierra's weirdest TV appearance was as a Jewish radical going up against Neo-Nazis, ultimately being killed by a bomb planted on his car, in a very special episode of..."All in the Family?" He also did an episode of "Ray Bradbury Theater" in 1992.

*** *** An obscure Howard Morris fact: he was the original voice of the Hamburglar on McDonalds ads. Robble robble!

**** *** Ice Cream Suit was also the final film appearance of Howard Morris, and the last one to date for Sid Caesar (unless you include his cameo in Comic Book: The Movie, if you can call that a movie.)

**** **** It is worth noting that the crowd begins to move away after applauding the suit, and are brought back by Villanazul's words. Also that the women who join Dominguez's parade are drawn to the music before they actually see the guitarist in his suit.

***** **** UPDATE: After the article was published, I heard from Derek Bruyere, second assistant cameraman on WICS and stepson of cinematographer Mac Ahlberg, who explained: "Mac had the gaffer build a custom ring light that, because of the suit material, made the suit sort of glow on film. We had a week of camera tests with it till we got it right."

***** ***** Another story from Gordon: "Once I was talking to an award group, I can't remember what the award itself was called but it had to do with Latino films. Ice Cream Suit was completely ignored, which amazed me. I finally talked to someone who was part of their organization, he said, 'Well you know, we don't want to show films that have Latinos living on the streets, or struggling. We want to show them as lawyers and doctors.' They were even concerned that the characters were speaking with accents. I thought, Didn't you consider that this is what it's like for most Latinos? But that's not the way they wanted to have them portrayed."

The origin of the film goes back to 1974 when Stuart Gordon, founding artistic director of Chicago's Organic Theater Company

The origin of the film goes back to 1974 when Stuart Gordon, founding artistic director of Chicago's Organic Theater Company